Keynote Speaker, Day One

Carol Taylor, PhD, MSN, RN, FAAN

Vulnerability and Trust: Why Who We Are Matters

“Be willing to speak the truth. Speak truth to power. That can take us out of our comfort zone,

but we’ve got to do it, and it gets easier with practice.”

Expand to read an interview with Carol Taylor.

Carol Taylor was interviewed by NNEC Planning Committee Member Brian P. Cyr, MSN, RN-BC.

The theme for the conference this year is “Everyday Ethics Rooted in Trust.” When you think about

“everyday ethics” in your various capacities as a nurse, as an educator, what comes to mind for you?

What has your experience been in keeping ethics front and center in your practice?

I always think about ethics as the formal study of who we ought to be in light of our identity. In that

sense, everyday ethics is about being what is reasonable for others to expect of us. That might be as a

human being, as a parent, or as a professional nurse. Our Code describes what is reasonable for the

public to expect of us. I worked with a group of nurse leaders once who said a good nurse is a

competent, compassionate, collaborative advocate for patients, families and communities. They’re

known for doing and making the critical difference. That’s a tall order, but that is what links me to the

conference theme. Can we be trusted to be that every day, speaking up when somebody’s not getting

the care that they need? Pretty simple, but still not easy.

I’ve been incredibly blessed because I did my PhD in Philosophy at Georgetown University and then was

invited to help start the Center for Clinical Bioethics for the Medical Center. That has kept me focused

on ethics as part of my everyday responsibilities. For 10 years, I directed the Center, so directed the

ethics consultation service design, the ethics curriculum for the medical school, and now I am teaching

full time in the School of Nursing and all my courses are on leadership and ethics. I am blessed to be able

to do that.

What advice would you give nurse leaders around building trust and trying to live up to that ideal?

The leadership course I designed was for DNP students and we really want them to be capable of

system-level change. One of the exercises that I had them do was to identify an ethics quality gap. It

might be our staffing never reaches appropriate standards to allow quality care. I expect the leaders to

fight for appropriate staffing to meet standards, and they have to describe how they were going to

assess it using Kotter’s ways to implement change effectively. What were the strategies they would use

to address the gap and bring things to a better place and sustain it. It was very practically designed.

From my very first nursing job, the chief nurse sold nurses out because part of being in the C-suite was

being a “yes” person and not standing up for nursing. I was appalled. That was one of my early

experiences of leadership, and I thought this cannot work. That is why I always say leadership really matters because if leaders don’t get it, you get ground underfoot pretty easily. It’s why people like you

are so important in the work that you do, to listen. Move it upwards with the people that are

experiencing the challenges.

The pandemic tested a sense of trust not only in healthcare, but in science itself. Moving forward, we

know that public health is a critical dimension in promoting wellness. How can we help to instill

amongst the public an awareness of both individual and community obligation to this ethical

endeavor?

This lack of trust in science really disturbs me. The extensiveness of it is relatively new. With the polio

pandemic, everybody knew what to do to eradicate it. Parents brought their children. Everybody was

vaccinated. Good people can reason differently about what ought to be done, but the purposeful spread

of misinformation is unconscionable to me.

I think we have to speak up whenever we hear statements that don’t comply with reputable science.

Pam Grace wrote an article about nurses and misinformation, and there are nurse leaders who are

trying to work through state boards to hold nurses accountable. We have nurse influencers on social

media sites, and we have to try to not be argumentative but persuasive

You shared the critical nature of nurses being vulnerable is needed to engender trust in the patients

and communities we serve. How does vulnerability fit into generating trust?

When Georgetown faculty articulated those four basic principles of bioethics – autonomy, beneficence,

non-maleficence, and justice – strikingly absent is vulnerability. It wasn’t until many years later that

when the European society identified their principles, they included things like vulnerability and dignity.

I was fortunate that a mentor for me was Dr. Edmund Pellegrino. He grounded the moral obligations of

healthcare professionals in three realities. The first was vulnerability. If people didn’t have healthcare

needs, they wouldn’t need nurses and physicians, right? If they could take care of themselves, they

aren’t contractual relationships. A nurse-patient relationship is not a contract among equals. It’s a

fiduciary relationship. I have to be worthy of the trust that the public places in me. I say to my students

all the time, most patients don’t choose their nurse. I go into labor. I present at the hospital. I get the

nurse that’s on that day. I get the nurse to whom I’m assigned. We need to be trustworthy. Patients

know right away if they can trust us or not or if they feel comfortable.

My husband was big on saying to people, “Tell me your story.” When you listen to people’s stories,

they’re pretty powerful. For example, right now there is so much in the literature about why black

maternal infant outcomes are so poor in the U.S. It’s not just socioeconomic status. Wealthy black

families have worse maternal infant outcomes. They learn quickly that they can’t trust the healthcare

system. It might be that institutional structural systemic bias that makes U.S. drug test black women

more often or makes us escort black men out of the hospital when they question the care that their

loved ones receive, and we think they’re being dangerous. All that makes trust so critical. Pellegrino’s

thing was grounding our moral obligations in vulnerability. The promise we make to work with people,

to be trustworthy, to help them improve their outcomes. Then actually working toward healing. That’s

been fundamental to me.

What advice would you give to frontline staff to develop and maintain trust among patients, families,

communities and other health disciplines?

Be willing to speak the truth. Speak truth to power. That can take us out of our comfort zone, but we’ve

got to do it, and it gets easier with practice. If a plan of care is not working for a patient, we need to

speak up. Our Code is big on nurses having a voice. I was giving a talk somewhere, and I’ll never forget

the nurse who said, “If you bring up a problem, you become the problem. So most of us try to fly under

the radar. You get paid the same for flying under the radar as you do for showing up and trying to be

that critical difference.” I was floored. If that’s the norm, that kind of thing rubs off. We expect you to

speak up. We did that with safety issues around medical errors. You see it. You say something and

you’re firm, even if you’re wrong. Whether it’s speaking up about racism or speaking up about a profit

motive or compromising the plan of care. This is our job!

Our choice of words can change the meaning of what we are attempting to convey. A good example is

discussing “withdrawing care.” Clinicians are aware that we never withdraw care at the end of life.

Adjusting that language to withdrawal of technology or treatment that is harmful or no longer

beneficial changes the conversation. Can you think of other examples of language that creates

misunderstanding?

I notice that none of my students talk about a patient “dying” or being “dead.” They always are

“passing” or they “passed.” What did they pass? Papers, gas? What does passing mean? Is that part of

our death denying culture that we can’t use the word the patient is dying? Last night, I was looking at

the November Hastings Center Report and there was a very interesting piece on medical assistance in

dying language and the acronym MAID. It is a way of referring to physician assisted dying. Other

countries like Belgium, Norway and Scandinavia have longer established practices where they refer to it

as assisted suicide, euthanasia or both. Far fewer deaths occur this way. That blew me away. If we call it

medically assisted dying, is that somehow just another way to die? It’s not. Physicians are writing lethal

prescriptions or administering lethal doses that cause the death. Language is incredibly important.

Plenary Speaker, Day One

Cynda Rushton, PhD, RN, FAAN

What Builds and Breaks Trust? Implications for Healthcare

Trust necessitates “recalibrating our relationship with the public from a social contract to a

social covenant. Our relationship with the public is bidirectional. It’s synergistic.”

Expand to read an interview with Cynda Rushton.

Cynda Rushton was interviewed by NNEC Planning Committee Member Karen Jones, MS, RN, HEC-C.

The theme for the conference this year is “Everyday Ethics Rooted in Trust.” When you think about

“everyday ethics,” what comes to mind for you? What has your experience been in keeping ethics

front and center in your practice?

Our values and commitments are consciously or unconsciously part of everything we do or say, so our

task in the distracted, divided world we are in is to stay connected to our moral compass and who we

really are. It really begins with trusting ourselves, to stay true to our values and our essences. Really,

that is the foundation for our ability to trust others. So, to me, everyday ethics starts with seeing the

world through the lens of values and commitments and developing our moral sensitivity to notice when

our values are at play, when they’re being upheld, and when they’re threatened. And when we start to

notice, I think that’s when it becomes part of everything we do.

The pandemic tested a sense of trust not only in healthcare, but in science itself. Moving forward, we

know that public health is a critical dimension in promoting wellness. How can we help to instill

amongst the public an awareness of both individual and community obligation to this ethical

endeavor?

I have been sitting with this question for a good while. During the pandemic, my wonderful colleague

Eileen Fry-Bowers and I wrote a blog for the Hastings Center focusing on this issue—trying to engage the

public in exploring what would happen if there were no more nurses. It has always been clear, but

especially during the pandemic, it was abundantly clear that nurses are the linchpin in the healthcare

system. The irony is that most people are only aware of nurses when they need health care. Clearly,

once a diagnosis is made, what people need most is nursing care. And yet at the same time, especially

during the pandemic, the level of disrespect and violence toward nurses escalated at alarming rates and

it’s persistent. I think this has created a profound shift in nurses’ relationships with the public. Especially

for nurses, that shift has eroded the strong bonds nurses have had with their patients. If you think about

it, when your patients turn against you, it is difficult to harness the fuel that you need to face adversity

that’s there every single day. Later, Eileen and I wrote an article about recalibrating our relationship

with the public from a social contract, which is how we’ve often talked about it, to a social covenant.

Our relationship with the public is bidirectional. It’s synergistic. I also had the chance to partner with

AARP and Susan Reinhart to propose 10 things the public could do to support nurses, starting with

figuring out what nurses do and how respect and trust is mutual, that both sides of the equation must

invest in it. Nurses are uniquely qualified to do certain things, but it’s in the partnership with patients

that we get the best outcomes. For example, patients taking the opportunity to get accurate and factual

information, asking questions, being advocates for themselves and not hesitating to notice the contribution nurses make every day to their care. One part of that is a simple thank you, but it’s also the

meaningful recognition that the DAISY Foundation is leading, fostering mechanisms by peers and leaders

to acknowledge the contributions nurses make every day. The DAISY Foundation, with AARP, recently

launched an effort to engage the public in sharing their experiences and gratitude for nurses, for the

contribution to their health and well-being. We are continuing that work in Maryland as part of our R3:

Resilient nurses’ initiative. Check out our website: https://nursing.jhu.edu/faculty-research/research/centers/r3/.

What advice would you give to frontline staff to develop and maintain trust among patients, families,

communities and the health professions?

Trust is a big topic; it’s very complex. We know it’s evocative. It has lots of different meanings based on

our own experience and our capacity to trust ourselves and others. A lot of the perspective I have on

this topic is really informed by more than 20 years of working with Dennis and Michelle Reina. It’s been

an incredible privilege to work with them. They have devoted their lives to creating trust and building

behaviors among individuals, teams and leaders. One of the things I really appreciate about their work is

that it focuses on behaviors, because trust is understood in the abstract, but where the rubber hits the

road is in behaviors. Their model includes three dimensions: trust of character, trust of communication,

and trust of capability. Within each of those are very specific behaviors that are associated with them. It

is not a theoretical idea. They have done a lot of research to validate their concept, and they have

measurement tools that can help clarify each of those levels where trust building is thriving and where

there are opportunities to strengthen it. The other part of the equation is we know trust is fragile, and

as human beings who interact with each other, betrayals big and small are inevitable. It’s just part of

being human. But that doesn’t mean that we excuse them. It means we must turn toward them and

have very specific strategies to rebuild trust when it’s been broken. There is a lot of emerging data in

nursing that documents the feelings of betrayal experienced by nurses particularly at the point of care

and the serious consequences in some cases of the moral injury that have resulted. This has been a part

of our research in the last couple of years, this concept of looking at moral injury as a more corrosive

and harmful type of moral suffering often involves some form of betrayal. There is a lot to unpack here,

and I hope everyone will join us to discuss the importance of trust in all aspects of our work in

healthcare. There’s a lot of opportunity, and it takes a sustained commitment to create the conditions

where trust can thrive.

Our choice words can change the meaning of what we are attempting to convey. A good example is

discussing “withdrawing care.” Clinicians are aware that we never withdraw care at the end of life.

Adjusting that language to withdrawal of technology or treatment that is harmful or no longer

beneficial changes the conversation. Can you think of other examples of language that creates

misunderstanding?

All of us are responsible for the words we say and what we repeat, because the words matter. Our

narratives have power. We need to be intentional about them. So here is what I say to my students.

Before you repeat the words and phrases that resonate for us, we need to pause and reflect before we

choose to repeat them. I like to use four filters for reflection on Is what I am about to say (1) true? (2) Is it beneficial? (3) Is it necessary? and (4) Is this the right time and place? If we are just repeating these

things out of nervous system activation, frustration, anger, fear, or outrage, we are inadvertently just

spreading that negativity in the words we repeat. So, noticing the impact on us, our bodies, our hearts

and minds is a good clue to determine what we should repeat or not.

There is a tendency when you’re under stress, when you’re exhausted, to think, “That’s right and that’s

wrong.” There’s no reflection. In a way, it’s a kind of release in the moment and it’s temporary, but the

consequences can be profound. For shift report, if it’s all negative – “We had a terrible day, this

happened, no one listened” – you start with your cup completely drained. There is no fuel for empathy.

There is no fuel for collaboration or listening or understanding. For me, it is people taking responsibility

for choosing how you want to show up, how you want to communicate, what is important. That requires

a pause before you speak.

One of the words that I think has really been misapplied and misunderstood is resilience. During the

pandemic, the resilience of nurses was highlighted again and again and yet it became weaponized by

some and shunned by others. It is unfortunate, because the problem is not the concept of resilience, but

how it’s being used. Resilience at its core is about how we face adversity, and there are decades of

research that document the inherent resilient capacity of every human in their physical, psychological,

social and moral dimensions. This whole narrative about “let’s not talk about resilience anymore” is

interesting. Every nurse I know is resilient. It is interesting to hear people think that cultivating resilience

is the sole responsibility of the individual. What we know about resilience in a social ecological

framework is we are all impacted in lots of different ways with our environment all around us.

Some people have cherry-picked partial definitions of the term to suggest it just means bouncing back.

The concept is much more robust than that suggests. There is no unifying definition, but one simple one

is our ability to flexibly adapt to recover, even grow in response to stress and adversity. Some suggest

it’s the ability to not only overcome setbacks but to move forward and go beyond the bouncing back to

learning and growing and transforming it. It’s a strengths-based approach rather than a deficit focused

one. Moral resilience, for example, is a protective resource to reduce the detrimental impact of both

moral distress and moral injury and even some mental health outcomes. That concept has always been

situated within a culture of ethical practice. We also see that the combination of moral resilience and

organizational effectiveness has the greatest impact on moral suffering, so it’s really when we add the

two dimensions together that we have the greatest opportunity to reduce some of the ongoing moral

distress or injury.

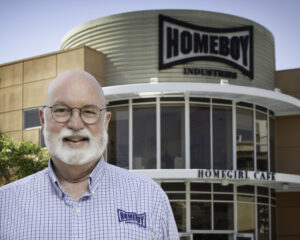

Closing Speaker, Day One

Father Gregory Boyle, S.J.

Cherished Belonging: The Healing Power of Love in Divided Times

“[We] need to invest in people and create together a community of cherished belonging.”

Expand to read about Father Boyle.

A native Angeleno and Jesuit priest, from 1986 to 1992 Father Gregory Boyle served as pastor of Dolores

Mission Church in Boyle Heights, then the poorest Catholic parish in Los Angeles that also had the

highest concentration of gang activity in the city. Father Boyle witnessed the devastating impact of gang

violence on his community during the so-called “decade of death” that began in the last 1980s and

peaked at 1,000 gang-related killings in 1992. In the face of law enforcement tactics and criminal justice

policies of suppression and mass incarceration as the means to end gang violence, he and parish and

community members adopted what was a radical approach at the time: treat gang members as human

beings.

In 1988 they started what would eventually become Homeboy Industries, which employs and trains

former gang members in a range of social enterprises, as well as provides critical services to thousands

of men and women who walk through its doors every year seeking a better life.

Homeboy Industries is the largest gang rehabilitation and re-entry program in the world. For over 30

years, they have stood as a beacon of hope in Los Angeles to provide training and support to formerly

gang-involved and previously incarcerated people, allowing them to redirect their lives and become

contributing members of their community.

This past May, Father Boyle received The Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States’ highest

civilian honor, from President Biden. “This recognition is heartening because it honors the many

thousands of men and women who have walked through our doors at Homeboy Industries since 1988. It

acknowledges their dignity and nobility and the courage of their tenderness. It underscores for us all,

the invitation to no longer punish wound, but seek its healing. It recognizes the need to invest in people

and to create together a community of cherished belonging.”

Father Boyle’s ministry through Homeboy Industries exemplifies the transformative power of

compassion, forgiveness, and second chances. For decades, he has empowered hundreds of thousands

of individuals to break free from cycles of poverty, violence, and incarceration. His unwavering

dedication to building bridges across divides and promoting understanding through compassion, kinship

and tenderness underscores the importance of empathy and connection in creating a more harmonious

society.

Learn more about Homeboy Industries: https://homeboyindustries.org/.

Keynote Speaker, Day Two

Aimee Milliken, PhD, RN, HEC-C

Recognizing and Addressing Ethical Issues in Everyday Nursing Practice: The Role of Ethical Awareness

“We can’t underestimate the power of storytelling…stories have a way of speaking to the

humanity within each of us and can help remind us of the humanity in others.”

Expand to read an interview with Aimee Milliken

Aimee Milliken was interviewed by NNEC Planning Committee Member Ellen M. Robinson, RN, PhD,

HEC-C, FAAN.

The theme for the conference is “Everyday Ethics Rooted in Trust.” When you think about “everyday

ethics,” what comes to mind? What has your experience been in keeping ethics front and center in

your practice?

For me, everyday ethics involves recognizing the ethical implications of everything we do as nurses. We

often teach about ethics in the context of big crises or dilemmas, but those situations make up such a

small portion of the actual work of nursing. Staying attuned to the ethical import of even seemingly

mundane tasks helps us to pick up on burgeoning ethical challenges early, when they are easier to

resolve. The idea that everyday ethics underpins the nursing role is foundational to my work about

ethical awareness. We need to be aware of the ethical implications of our actions in order to address

ethical issues when they arise, and to notice recurring problems that require a preventive ethics

approach. This work is critical to addressing sources of moral distress, as well.

The pandemic tested a sense of trust not only in healthcare, but in science itself. Moving forward, we

know that public health is a critical dimension in promoting wellness. How can we help to instill

amongst the public an awareness of both individual and community obligation to this ethical

endeavor?

We can’t underestimate the power of storytelling. We know that people aren’t often swayed by the

introduction of statistics and other fact-based information when it challenges a deeply held worldview.

That said, I think stories have a way of speaking to the humanity within each of us and can help remind

us of the humanity in others. In this way, narrative ethics can be a useful tool to help us see past

ideological differences and remind us that we have care-based obligations to the people we are in

community with, even when we disagree with one another.

What advice would you give frontline staff to develop and maintain trust among patients, families,

communities and the health professions? What advice would you give nurse leaders? Hospital

administrators?

In my opinion, developing and maintaining trust requires open and direct communication. We need to

be sure to acknowledge uncertainty, and to be humble about what we know for sure and what we do

not yet know. This is a big ask in our fast-paced and highly technological environments of care, and “grey

areas” are uncomfortable places to sit. Acknowledging that grey when it exists is so important. We also

need to acknowledge when the system has failed – our patients, our colleagues, and ourselves. Being

honest in the challenging times when we wish we could do better, or when we wish we had better

options to offer, is a critical piece of this. We know that our healthcare system has profound limitations

and unfortunately our patients, especially our most vulnerable patients, often suffer the consequences

of that. Starting from a place of acknowledging these shortcomings, even if we can’t immediately fix

them, is a difficult but necessary first step.

Our choice of words can change the meaning of what we are attempting to convey. A good example is

discussing “withdrawing care.” Clinicians are aware that we never withdraw care at the end of life.

Adjusting that language to withdrawal of technology or treatment that is harmful or no longer

beneficial changes the conversation. Can you think of other examples of language that creates

misunderstanding?

There are so many examples within the healthcare lexicon of phrases that inadvertently create

misunderstanding and even contribute to mistrust. I often think of code status discussions when we ask

families if they want us to “do everything” for their loved one, and we get frustrated when the answer

to this question is “yes.” It is human nature for a loving family member to want a team to “do

everything” – but if we aren’t explicit about what we are asking, we can end up pursuing a plan of care

that feels medically inappropriate and incongruous with the patient’s actual goals and values. I also

think about “fighting” analogies in the context of terminal illnesses like cancer. While fighting is a noble

and worthy goal, this framing can also inadvertently send the message that transitioning the goals of

care to a focus on comfort is “losing,” when we know in actuality this is a transition that requires

courage and bravery as well.

Kara Curry, MA, RN, HEC-C

Shika Kalevor, MBE, BSN, RN, HEC-C

Plenary Co-Speakers, Day Two

A New Era of Ethics: The Power of the Code

“Ethics isn’t only about the big, dramatic dilemmas and conflicts we encounter, but it’s also in

the care we provide, the medications we give, how we teach, how we advocate, and the way we

humanize the people we encounter on a day-to-day basis.” – Shika Kalevor

Expand to read an interview with Kara Curry and Shika Kalevor.

Each of you were involved in the 2025 revision of the ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses. How are the concepts of everyday ethics and trust a part of the “new era of ethics”?

Kara Curry: This new era of ethics must match the intensity of the changing healthcare landscape that surrounds us. Issues of harm against patients require the longstanding value of human dignity to extend to condemning dehumanization. Heightened workplace violence results in the need for safety in the workplace, but that now extends to safety in patient encounters and collegial relationships. Recognition of bias as a contributor to health inequities and health disparities requires intentional self-reflection of nurses and the nursing profession. The duty the nurse has to themselves extends to the nurse’s ability to flourish and thrive. The structures and systems in place resoundingly affect patient outcomes which is why health policy must be recognized as social policy. All of these dynamic issues that are part of our

everyday ethics come with an intensity and urgency that make this new era of ethics as important as it’s ever been.

Shika Kalevor: This new era of ethics for nursing recognizes that the nurse practices and upholds the Code in everyday interactions with each other, their patients, themselves, and society. This iteration of the Code is not only aspirational, but also in touch with the everyday realities of nursing practice in its various forms. Ethics isn’t only about the big, dramatic dilemmas and conflicts we encounter, but it’s also in the care we provide, the medications we give, how we teach, how we advocate, and the way we humanize the people we encounter on a day-to-day basis. As a highly trusted profession, this Code honors that trust by using moral courage to address some of the most challenging things we face as a profession and a society.

Closing Speaker, Day Two

Marilyn McEntyre, PhD

It Matters How You Put It: Words and Wellbeing

“Words can be lifegiving. What can I offer that is lifegiving here? What words wake people up?”

Expand to read an interview with Marilyn McEntyre.

Marilyn McEntyre was interviewed by NNEC Planning Committee Member Beth Kohlberg, MEHCE, BSN,

RN, HEC-C.

What advice would you give to develop and maintain trust among patients, families, communities and

the health professions?

Words can be lifegiving. What can I offer that is lifegiving here? What words wake people up? What

helps us dig down under the layer of cliches and white lies? Black and brown Americans often distrust

medical institutions. How do nurses help them and say, “This system isn’t serving you well. What can we

do about it?” An acknowledgment is important. Systems don’t always serve people well. Consider

asking, “Who are you? What will be harder for you now when you go home?” Get to know individuals.

Open up a conversation and step outside the “I am the nurse. You are the patient.” Find ways to say, “I

see you. I value you. I wonder about you.” When speaking to patients, take the judgment out of the

conversation. Pay attention to words like, “I noticed…” or “I see…” or “I hear you say…”.

I encourage my students to pause over a word or interact with just one word. For example, John Lewis

said, “Get in good trouble. Necessary trouble.” If we are to pause over the word trouble, what does

trouble mean here? Explore just that word and the impact that “trouble” has. I also use poetry when I

teach medical students to help doctors pause, to be comfortable pausing, and to find the right words for

a specific situation.

Pick a word that stands out. Not a sentence, phrase or paragraph; but one word. They must share why

that word made a difference. I want students to look at the glass, not at the window. If you do that,

something happens. You get to the “musical” level of language.

Our choice of words can change the meaning of what we are attempting to convey. A good example is

discussing “withdrawing care.” Clinicians are aware that we never withdraw care at the end of life.

Adjusting that language to withdrawal of technology or treatment that is harmful or no longer beneficial changes the conversation. Can you think of other examples of language that creates

misunderstanding?

We are in a culture and society that commodifies everything. People “generate” words instead of

thinking about how words can be inviting, enticing, and inspiring. We are all operating in a contaminated

language environment. It is profit-driven, politically associated, and there is social media shorthand.

Speaking a word can invigorate us and challenge us. For example, in the political climate today, if you

call an immigrant an “illegal,” it obscures their humanity. It makes it harder to see them, harder to hear

them. It can be deceptive.

What does that mean for those in medicine? Other examples are when people use metaphors for

suffering. A “battle with cancer.” Your body is not a battleground. Change the language to a “journey

with cancer.” “Loss” is seen as a failure in this culture, but we all die. “End of the journey” is a more

gentle way of saying it.

Words are an instrument of our work.